On reading the abundant attention-grabbing headlines regarding Australia’s supposed debt crisis, it would certainly be easy to feel uneasy.

Headlines, by their very nature, are designed to pique our interest, to make us believe the article in question has some new, interesting or shocking thing to say. Otherwise, why read it at all?

However, it could be that when we drill down and look at all of the research and statistics available, the overall picture of household debt in Australia may not be as bleak as the headlines would have us believe.

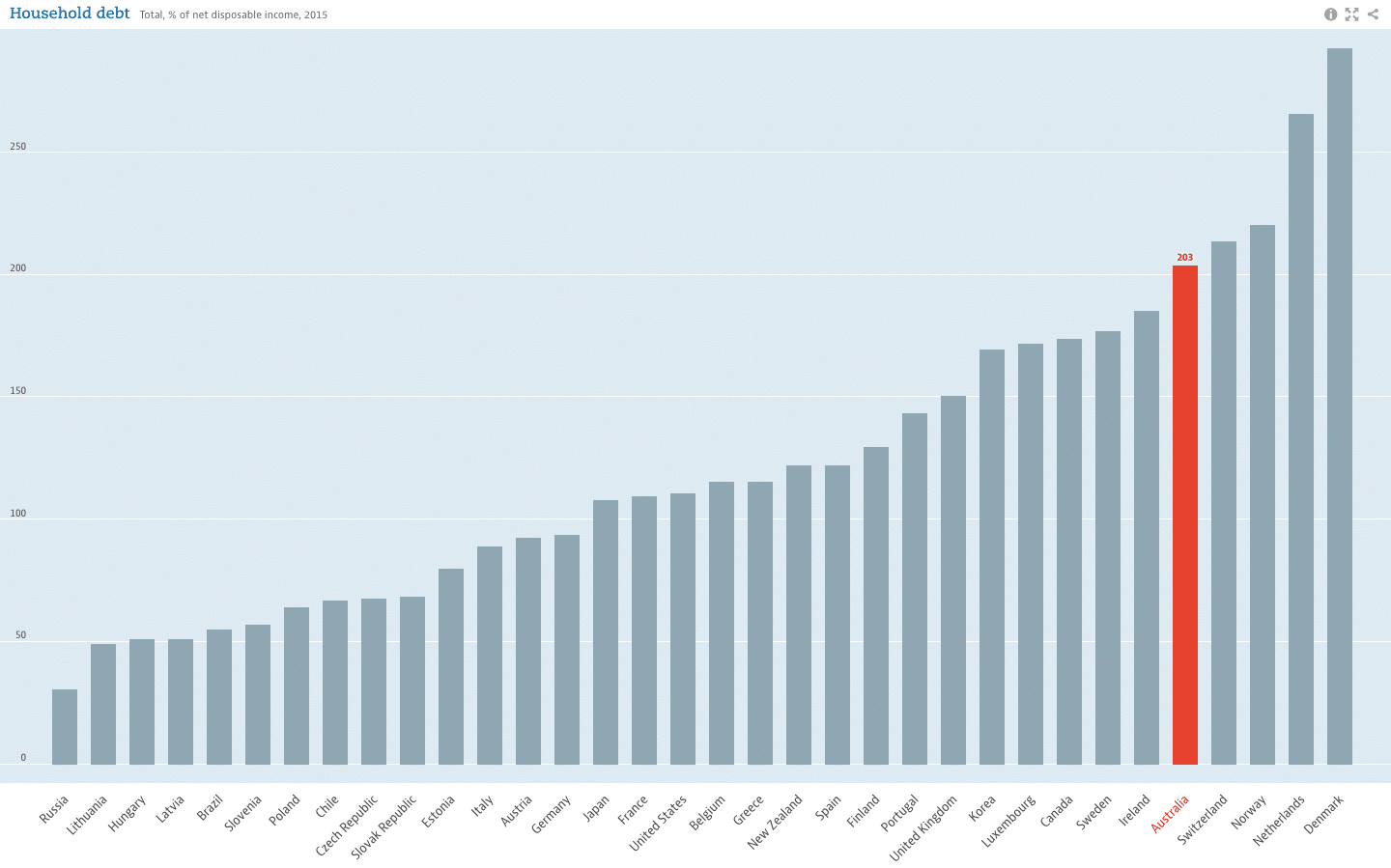

To be fair, it doesn’t look that great at first glance. According to the most recent global statistics available from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Australia ranks fifth highest in the world according to total household debt owed as a percentage of net disposable income.

Source: OECD (2018), Household debt (indicator). doi: 10.1787/f03b6469-en (Accessed on 01 August 2018)

What is the household debt for most Australians?

To understand why these figures can sometimes be misleading, it’s essential to look at how household debt is calculated and what it includes. With total personal debt in Australia at around $2 trillion as of 2016, the average Australian household owes $250,000. This can be broken down into the following categories:

| Mortgages | According to Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) data analysed in the AMP.NATSEM report, mortgages for owner-occupier housing makes up 56.3% of all personal debt in Australia. |

| Investor debt | Investor debt, made up of debt associated with investments, such as shares and rental properties, makes up 36.5% of Australian household debt. |

| Personal debt | Personal loans, taken out to pay for things that may not be otherwise affordable, such as cars, holidays and other consumer items, make up 3.1% of Australian household debt. |

| Student debt | Student loan debt makes up 2.1% of Australian household debt. |

| Credit card debt | Debt on credit cards makes up 1.9% of all household debt. |

While the amount of debt as a whole may sound risky, it’s important to look at the way in which that total can be broken down. On a very simple level, Australian debt can be split into ‘good debt’ and ‘bad debt’.

The difference between good and bad debt

Good debt could be thought of as debt you would take on to allow you to build wealth in the long term. This could be a home loan that allows you to eventually own your own home, or an investment property mortgage that lets you boost your monthly income in the short term, with the potential to re-sell the property at a higher price later on.

On the other hand, bad debt occurs when you borrow to pay for things that don’t provide a financial return, and that you couldn’t otherwise afford. Working to reduce your wealth over time, this could be credit card debt or a car loan.

So, if you break down Australian personal debt in this way, you can see good debt stands at 92.8%, while bad debt is at 7.2%. With that average household debt at $250,000, the average percentage of bad debt would be $18,000.

While that’s still not ideal, it’s worth noting that data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York shows that ‘bad debt’ made up 26.3% of the United States’ personal debt in the first quarter of 2016 (1).

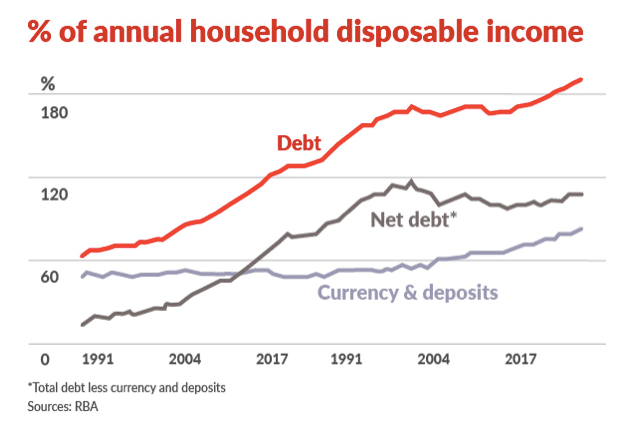

When looking at personal debt in Australia, understanding the difference between gross debt and net debt is important. While it is usually the gross debt total that’s reported – perhaps because it makes better headlines – it’s really net debt that counts.

What do you need to know about gross debt vs. net debt?

Net debt is what we have in loans minus what we have on deposit and in cash. The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) tends to report on gross debt as a percentage of disposable income.

As you can see from the graph above, it doesn’t paint the prettiest picture.

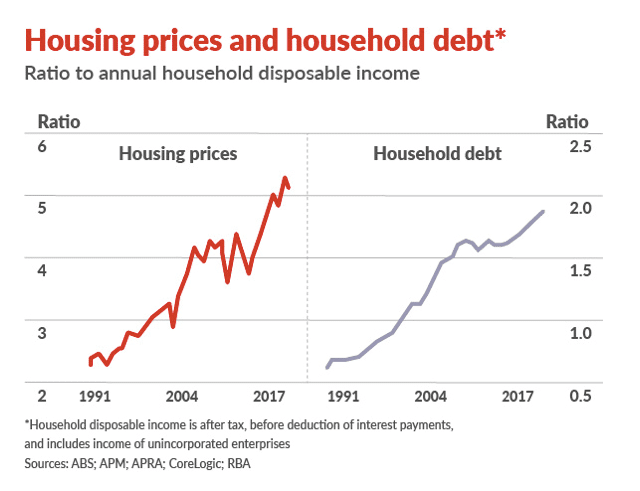

While still highly relevant, one of the main reasons the RBA found we have a high level of household gross debt compared to other countries could be attributed to the fact that most of Australian rental housing is owned by households, rather than companies or the government.

And as anyone who has checked out the housing market in their local area knows, property tends to be expensive.

What may be more helpful is to look at household net debt instead. According to the Commonwealth Bank’s annual results last year, unlike Australia’s gross household debt, which has been on the rise, net household debt peaked some years ago and has been more or less stable ever since.

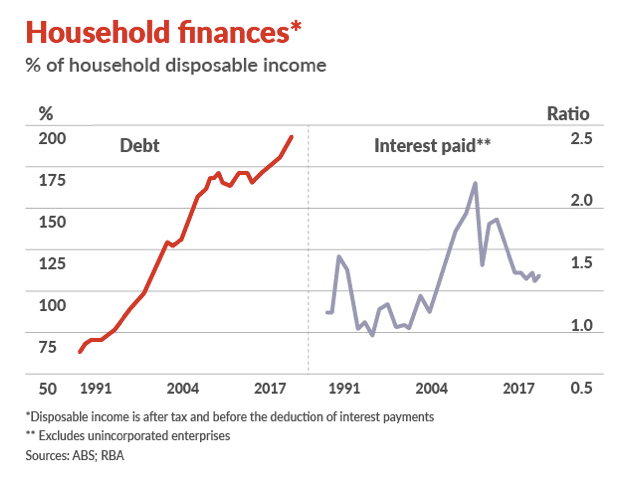

It could be argued that the amount of debt we have is not the issue. Instead, it’s the serviceability of that debt. As the below graph shows, debt as a total has grown, but the interest paid on that debt (as a percentage of household disposable income) has fallen.

On this point, though, it is worth noting two things. Firstly, interest paid on those increased levels of debt has stayed relatively manageable because interest rates have remained low. The RBA has kept Australia’s cash rate on hold at 1.5% for two years now, with the last change made on 3 August, 2016 (2). This, in turn, has kept the typical ratio of debt interest repayments to disposable household income at around 6%, as shown in the AMP.NATSEM report (3).

Secondly, there is the potential for personal circumstances to change. Good debt can turn to bad debt when a property loses value instead of gains value or, when personal circumstances change – due to divorce, redundancy or illness, perhaps – loan repayments can become unmanageable.

This is why it’s also important to look at risk when assessing Australia’s personal debt levels. Looking at the ratio of income growth to personal debt, Australia’s personal debt levels have now exceeded income growth, creating a debt-to-income ratio of 88% (4).

Demonstrating there is some cause for concern. An increase in interest rates, or a steep decline in the property market could make it much harder for people working to pay off debt. However, it’s unlikely the RBA will increase the cash rate until the average income also starts to grow.

As for that ticking property time bomb, it could be said it’s more of a property clock, and understanding how to read the property cycle clock plays a large role in weighing up risk and your investment strategy.

No one is denying there is room for improvement for Australia’s rates of household debt however, it’s important to remember that the situation may not be all doom and gloom. For more on Trilogy’s opinion on the current state of the market, check out our market insights available on the blog.

[1] https://www.finder.com.au/australias-personal-debt-reported-as-highest-in-the-world

[2] https://www.rba.gov.au/statistics/cash-rate/

[3] https://www.finder.com.au/australias-personal-debt-reported-as-highest-in-the-world

[4] https://www.finder.com.au/australias-personal-debt-reported-as-highest-in-the-world

The material on this website is intended only to provide a summary and general overview on matters of interest. Trilogy is only licensed to provide general financial product advice on its own products and does not consider your objectives, financial situation or needs when providing any information or advice. You should consider whether the advice is suitable for you and your personal circumstances and we recommend that you seek personal financial product advice on your objectives, financial situation or needs and obtain and read the relevant product disclosure statement before making any investment decision.